Cook Island Medicine.

2016, Rarotonga, The Cook Islands.

I was peeling my motorcycle around a sandy bend of road on the coast when I saw a jet aircraft coming over the horizon to my right. Flights didn’t come in very often, so I took the opportunity to peel off the curb into the sandy shrub, and wait for the plane to land. I walked up to the chain link fence at the boundary of the airport to get as close to the touchdown point as possible. When the planes came in, they came down hard and fast, and tourists loved feeling the force of engine air push them away from the fence.

I suppose that it wouldn’t be allowed in Melbourne, since someone would inevitably toss a 50c coin up into the turbines just to see what would happen.

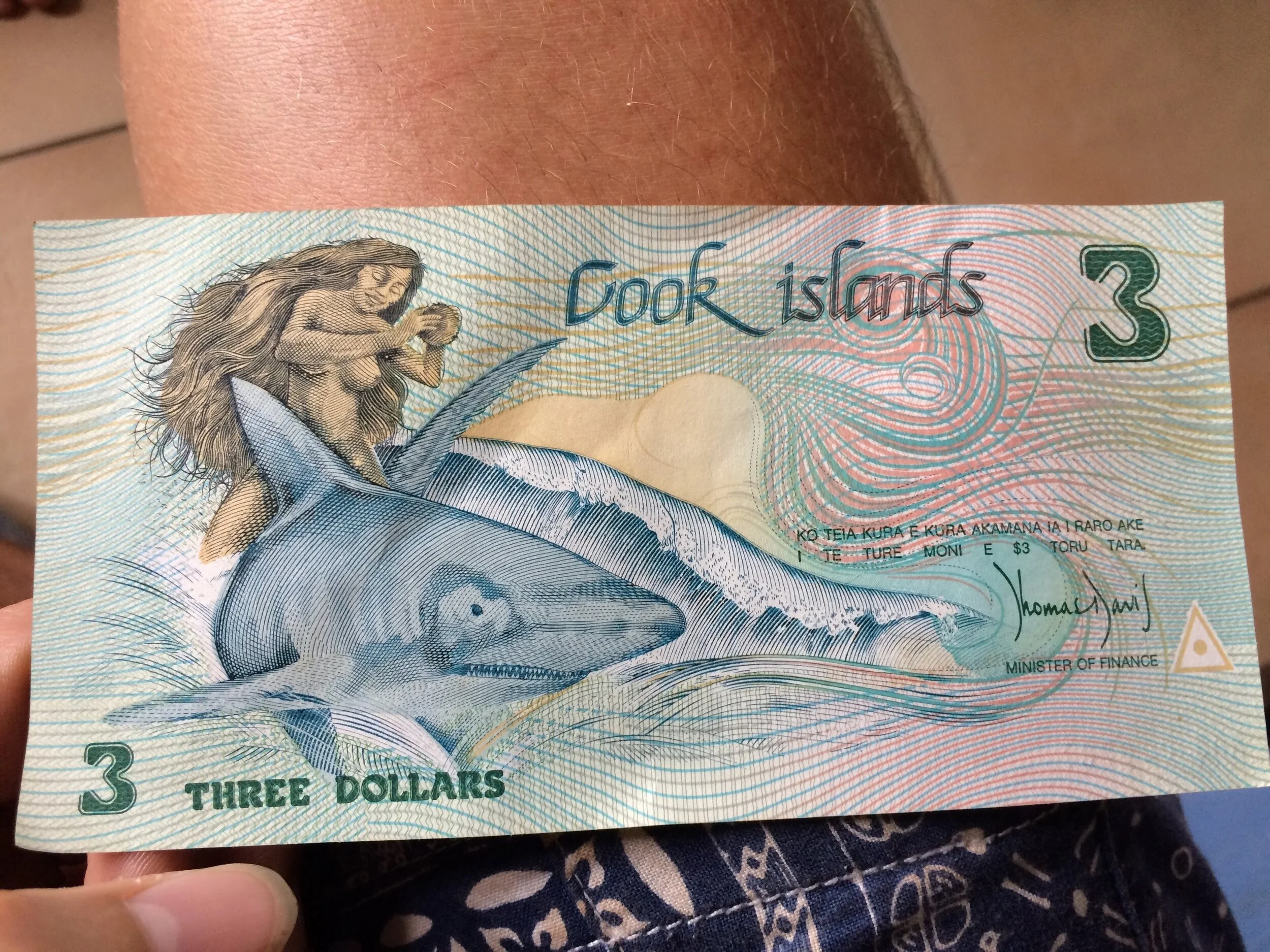

The Cook Islands currency, on the other hand, isn’t hurting anyone.

When I arrived at the fence, I saw a woman there waiting with a camera. We started chatting about the island, and I got the sense she was very like many other women lazing around in hammocks at my hostel.

German, so she’s rich.

Single, so she’s travelling.

In her late 20s, because no early 20-something in her right mind would spend $2000 to fly to the Cook Islands when you can Eat, Pray, Love in Bali.

And very very bored of taking pictures of sunsets.

So she was very interested in why I was wearing scrubs and had a hospital ID badge dangling from my neckline.

I’m on my way back to to the hospital. They’re teaching me how to deliver babies.

“Oh. My. God. That is. Amazing.” she replied. “What’s it like? Is it just, so amazing?”

And they say baby talk doesn’t work on women.

She had a million questions, which I was tired of answering. The realities of delivering babies involves a lot of waiting. It’s like working with the world’s most obnoxious surgeon. He takes ages to arrive, and everything seems to be going ok until he suddenly does something which kills someone.

Yeah… it’s not always like the movies, I said, gazing sadly into the distance. I was hungry - I’d only eaten two hamburgers that day. Blood takes away my appetite.

She put a consoling hand on my shoulder. “It sounds like you’ve been through a lot.” I felt her hand give a reassuring little squeeze.

Oh great, she thinks I’m haunted by my past, and now she’s going to heal me!

When I get that feeling, I want professional healing. Professional. Heal-ing.

“Having been through all that, would you still say - I mean, it’s obviously not going exactly to be exactly what you thought - but would you say that it’s what you expected when you came here?”

I noticed the ying-yang around her neck, the om tattoo on her wrist. The too-intense stare. I felt like I was about to get a hug and a nose full of turmeric scent.

Not at all. I said. In fact, it’s hard accepting the reality.

“Really? How is it different?” She asked, her eyes searching for a masculine mystery in my hard-set visage.

I sighed.

Well…

I thought I’d be arriving on a light aircraft, you know, something with propellers. As the plane landed, the locals would scramble around in terror trying to make sense of the technology they were seeing.

The wise chief would come to the stairs of the plane to meet me, and thank me for bringing medicine to the children of his village. I thought that he’d invite me to his home and insist I sleep in his bungalow guestroom, and eat swordfish with his family.

By day I’d cure islanders of rare and dangerous tropical diseases, and by night I’d teach his exotic but intelligent daughter about Australian culture so that she could study nursing at Melbourne University. One day she’d return to lead her tribe with me beside her to advise her as her island doctor.

But in reality I’m just standing there for hours holding a bucket.

She stared at me with an expression of politically correct horror.

Me being taught advanced techniques in getting up someone’s nose.

In comedy, timing is everything, and I’ve always felt like time was on my side. Just at that moment the Air New Zealand plane roared out of the sky.

She politely looked pointed, smiled, and indicated that we should watch. My hospital polo was filled with hot air. The plane seemed to hang in the air like the silence between us.

Well! See ya! I said, putting on my helmet and jumping back on the motorcycle.

“Wait!” she shouted, “I don’t mean to sound offensive, but… were you serious about that?”

About what? I asked.

“The whole wise chief thing...meeting you at the plane”.

Oh that? No. Of course not. I laughed.

I thought that was obvious.

I opened the throttle and went home to watch a Love, Actually VCR on my little hostel television.

And if you want more, if you want more, more, more, then -

Here’s what I wrote about it in 2016.

Ah… takes me back.

In November 2016 the Andrew Dent Elective Scholarship enabled me to travel to the Cook Islands to study for a month at the hospital on Rarotonga. Sitting down to write this report has been an absolute pleasure because it brings back so many memories of medical cases and island life I had not thought about in months. Rarotonga is a wonderful place to study and the standard of medicine delivered to the people there is excellent, which is a great credit to the diligence and care of the medical staff and allied health. I’d like to extend a sincere thanks to those doctors, nurses, ambulance officers, and administrators who took the medical students under their wing during our visit.

There are two ways to visit Rarotonga hospital as a patient. One is to take a motorcycle or car up the side of the mountain to the hospital plateau and then take a seat outside a clinic where you can watch chickens popping in and out of the jungle. The other way to visit the hospital is in the back of an ambulance, which routinely races at a swift 70km/hr around the island circuit road in response to emergencies. I had just stepped out of a screening of Moana at the local cinema (it had the schoolchildren in hysterics) when I saw a bleeding man being tended to by the hospital IT manager. The picture was not pretty. A mangled motorcycle, a head injury and an unresponsive patient had me nervously wringing my stethoscope until the ambulance pulled up. I asked the Doctor riding along whether the low Glasgow Coma Scale could be due to an epidural haematoma, to which he laughed and told me to smell the patient’s breath. I had forgotten that alcoholic coma was a differential diagnosis! The patient made a full recovery after a night of vigilant observations but had no memory of our meeting.

The last thing you see before the green whistle hits.

The diversity and vibrancy of the medical presentations in the Cook Islands was compelling. In paediatrics we saw bronchiolitic babies being soothed with nebulizers alongside restless teenagers with fractured tibias who struggled to pass time in recovery. In OBGYN we saw natural births, C-sections, and stood with generous doctors as they tutored us on how to use the ultrasound machine. The end result of which was that some of us could say definitively in the third trimester whether the head was ‘up or down’.

The outpatient clinic was where medical students were put to the test. On day one I was asked which treatment I recommended for a gouty toe. I blurted out “NSAIDs” and was quite pleased that I could recall reading it in the Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine the week before. Meanwhile, the doctor stood there puzzled and then asked me whether I intended to indicate a dose, or did I want to leave that up to the patient. My answer had only been “acceptable for an MD2” – a clear signal that I needed to lift my game. Over the next week it became necessary to brush up on treatments for asthma flares, diabetic ulcers, and infections of all kinds. Medical students were allowed to ‘parallel consult’ in rooms of their own and discuss prescriptions with doctors. The independence encouraged a high standard of clinical reasoning which was immeasurably valuable for our learning. It was especially rewarding to see that patients who came in for follow-up requested the same medical students from their first appointments. Additionally, when thank you notes were mailed in, we pinned them to the wall in the common area. Sometimes the addressees were long departed, but we had glimpses into the previous students’ clinical experiences.

The culture at the hospital was very social. In early December all medical students were invited to a ‘family day’ at the beach. The entire staff of the hospital showed up with children in tow to have a feast and compete in games. There was a competition to see who could open a coconut first and carry it out to sea. The greatest tug of war match of all time took place in the shallows, as children leapt out of the way to escape falling parents. During the volleyball game there were several amazing burns (both verbal and dermal). I spent a long time with one of the cooks trying to get down a recipe for the “poke” pudding that tasted like heaven in a bowl. It seemed to change every time I asked – but I gathered that the main ingredients were bananas and every carbohydrate known to botanical science.

Who wants high dose prednisolone?

On one of the off days I organized with another medical student to visit the local herbal medicine practitioner and island trekker, Pa. He would point to the formidably high peaks on the island’s interior and say, “When I was six, I was on top of that mountain by myself”. Pa was perhaps the original architect of ‘alternative facts’; it was impossible to separate the personal history from the myths. He took us on a trek up the mountain and gathered chillies, soaps, analgesics, and flowers from the path as we went. So many of the Cook island residents suffered from obesity and diabetes due to a high calorie diet. Pa was the opposite. He ate a huge amount of fruit and fish, foraging most of his meals from the jungle. When we arrived, he was fermenting “Noni juice” which he was adamant would be the next huge healthy eating trend. It smells like blue cheese and tastes like… words fail me. Perhaps he was right though. Pa was a healthy sixty-year-old who looked forty. At one point he claimed to have shocked the hospital by lowering his blood cholesterol from high to “unreadably low levels” by consuming a bulb of raw garlic per day (“It HAS to be raw”). He encouraged us to look up his results at the hospital. It is with great regret that I admit I forgot to check the records before I left.

My colleague hearing Pa describe how he had performed an exorcism on a demon that was haunting the island ringroad by setting it on fire with petrol.

Travelling to the Cook Islands as a student was liberating. Looking back, I am almost embarrassed to recall how much assistance and time was given to us medical students out of the graciousness of our host hospital. Thank you again for the scholarship which gave me the opportunity to study in one of the most beautiful places in the world.